Following our first investment in space and satellite tech, Lookup, we’ve been taking the time to dig deeper into the category and its evolving dynamics. We’re still early in our journey; learning, asking questions and updating our mental models as we go, but we wanted to share a first sketch of what’s capturing our attention. We’ve learned a lot from our extensive conversations with Silviu Pirvu FRSA and our friends at Arkadia Space and FOSSA Systems, but please reach out to pablo@kfund.vc or paula@kfund.vc to share your thoughts, feedback and perspectives as we keep exploring.

For some time, “SpaceTech” was often shorthand for “not our mandate.” Not because the ideas lacked merit, but because the risks seemed outsized, the timelines too long, exit pathways unclear, and the capital requirements over time exceeded the scale of our funds. When we heard “space,” we thought of enormous upfront costs, long R&D cycles, regulatory red tape, and decades of government-driven procurement. Even for funds with an appetite for frontier tech, space often sat just beyond the edge of what felt feasible.

But that framing is starting to shift, and not just for us. As our portfolio company Lookup puts it, the industry is evolving from an era of expensive launch and manufacturing into a more service-oriented, infrastructure-like model. Hardware remains critical, and there is significant innovation in areas like solar arrays, propulsion, and power management systems. At the same time, we see a major unlock at the data, integration, and workflow layers, where space becomes an enabler for adjacent sectors such as defense, insurance, energy, logistics, and mobility.

What used to feel like a highly specialized, capital-intensive domain is slowly becoming more modular, more software-driven, and most importantly for us, more investable. This change is not happening overnight and not without caveats but the distance between what’s happening in space and the industries we know well is closing.

This post is a working view of what feels like a turning point, where technical abstraction, commercial demand, and a new generation of startups are coming together to redraw the landscape.

Until recently, tapping into space-based assets meant working through long procurement cycles, complex hardware, and massive budgets. Now, that’s changing. Just as cloud abstracted away server management, a new generation of companies is abstracting the complexity of space. You no longer need to build or operate a satellite to benefit from it. Increasingly, you can:

This shift, from raw hardware to usable platforms, is making space relevant to entirely new user groups.

Now, while this transformation is real, it’s worth recognizing that the fundamental structure of the space economy has remained over time: satellites collect data, space tech companies process and deliver that data, and downstream businesses across industries like agriculture, defense or logistics, use it to inform decisions and power services. That loop hasn’t changed. What’s changed is how efficiently, affordably, and flexibly each part of that loop can now operate.

Several enabling technologies and have accelerated this shift:

Launch and satellite building costs were long a bottleneck on satellite deployment, but over the past two decades the dynamic has shifted, with thousands now launched each year. We are entering an era of far more affordable space infrastructure. The result is a larger and more diverse orbital fleet, creating a broader and more accessible data ecosystem, and with it, business models that were never conceived before.

So while satellites and other physical infrastructure remain central, what’s changed is how much easier it’s become to access and work with that infrastructure. APIs, onboard compute, and integration tools have further removed layers of complexity. Space is no longer just for governments and deep-tech primes, and that shift is what’s opening the door to new commercial use cases and broader investor interest.

A few companies building the underlying tech driving this shift that stood out to us:

Collectively, these examples point to the same shift: value is increasingly captured not just in the hardware itself, but in the layers that make space infrastructure easier to deploy, integrate, and use across industries.

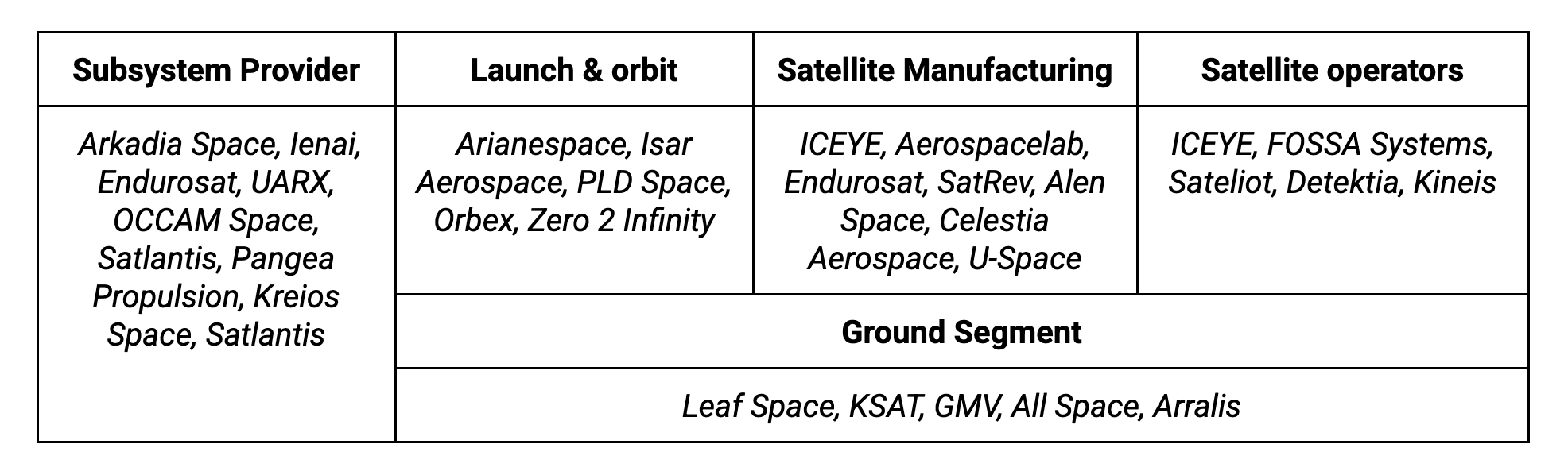

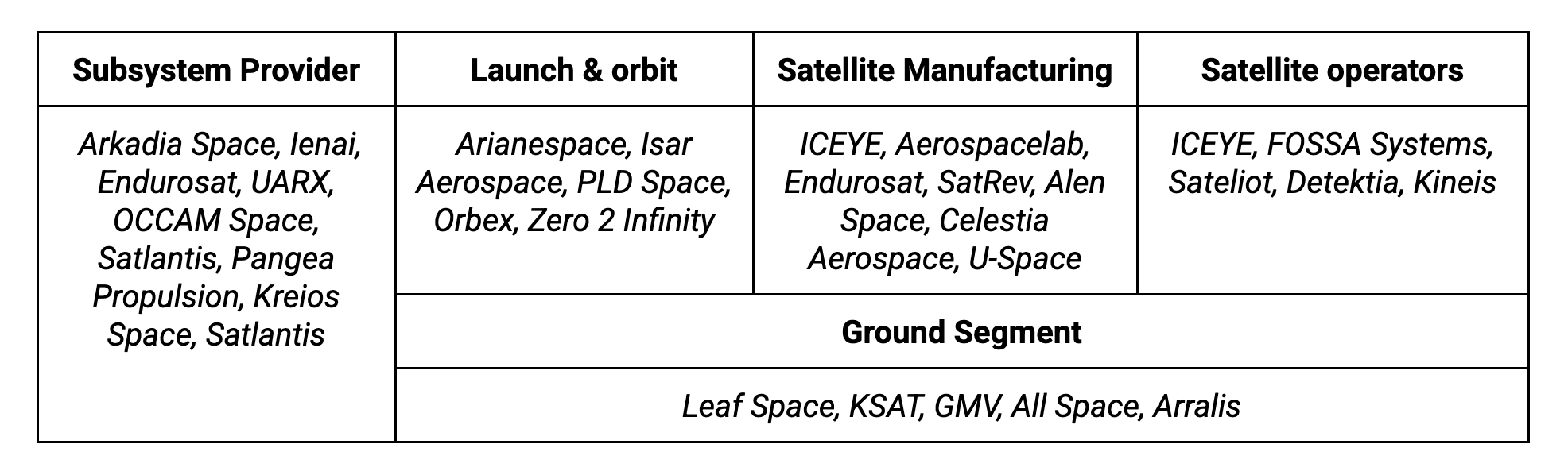

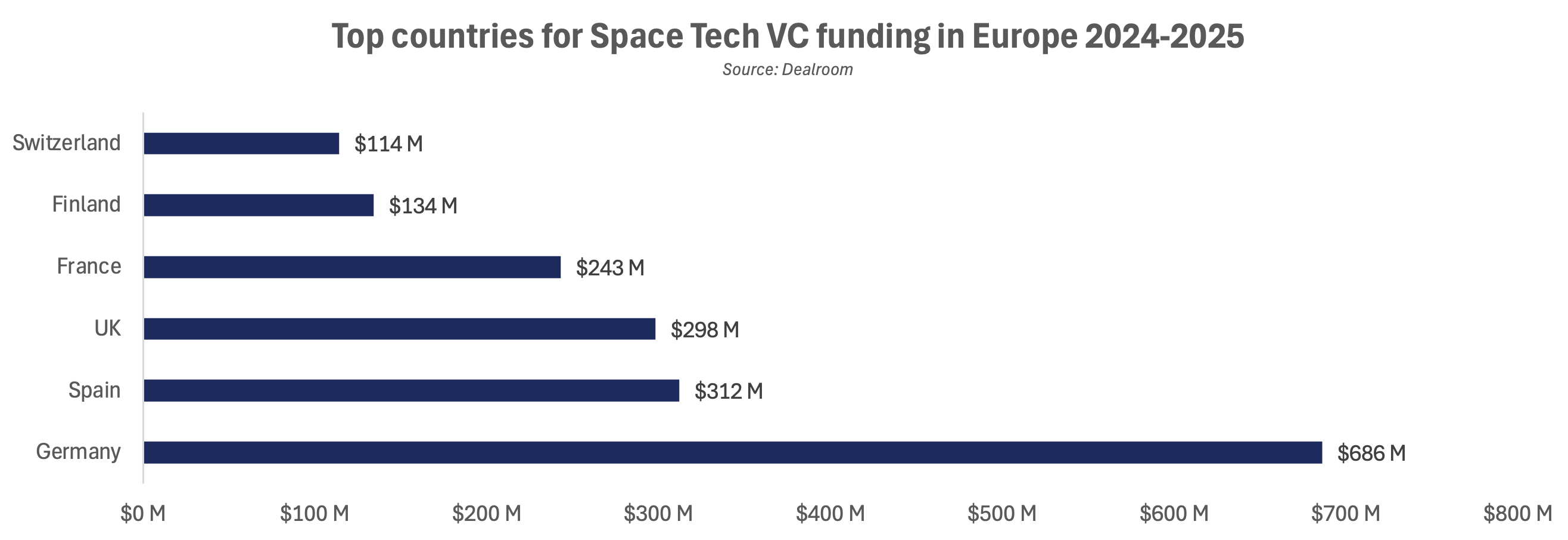

This is how we currently view the industry, with some illustrative examples from Spain and the rest of Europe. We’re still learning, and would love your thoughts on other ways of viewing the taxonomy of the landscape:

Core infrastructure providers

The upstream enablers positioned in service of end-user outcomes

Enabling platforms & middleware

Companies that abstract complexity and make space data useful across verticals

As space infrastructure becomes more abstracted and accessible, its value is increasingly defined by what it enables on the ground. This isn’t just about satellites in orbit, it’s about insight at street level. The most exciting momentum is happening in the tools, platforms and workflows that deliver space-derived intelligence to its real users: governments responding to crises, insurers pricing risk, farmers optimizing yield and logistics teams navigating port delays.

As Silviu Pirvu FRSA, Chairman & CTO Optimal Cities puts it: “The world is continuously changing, in some places faster than before. Shaping a healthy and thriving future needs reliable, actionable perspectives to ensure the resilience of people, assets, and environments. Delayed decisions lead to their obsolescence, with ripple effects in society, economy and environment. When combined with AI and user friendliness, SpaceTech can be a critical ally for authorities, decision-makers, professionals and emergency responders in enabling fast, decisive action - from Earth Observation to real-time communications, energy beaming and safe orbits.”

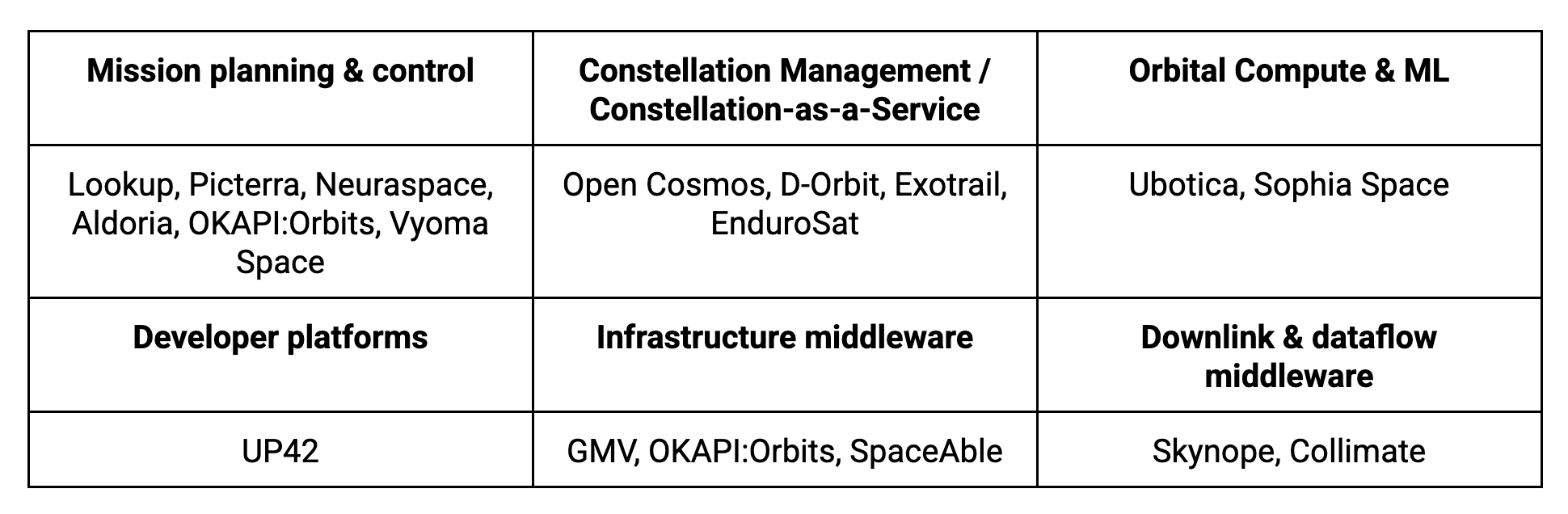

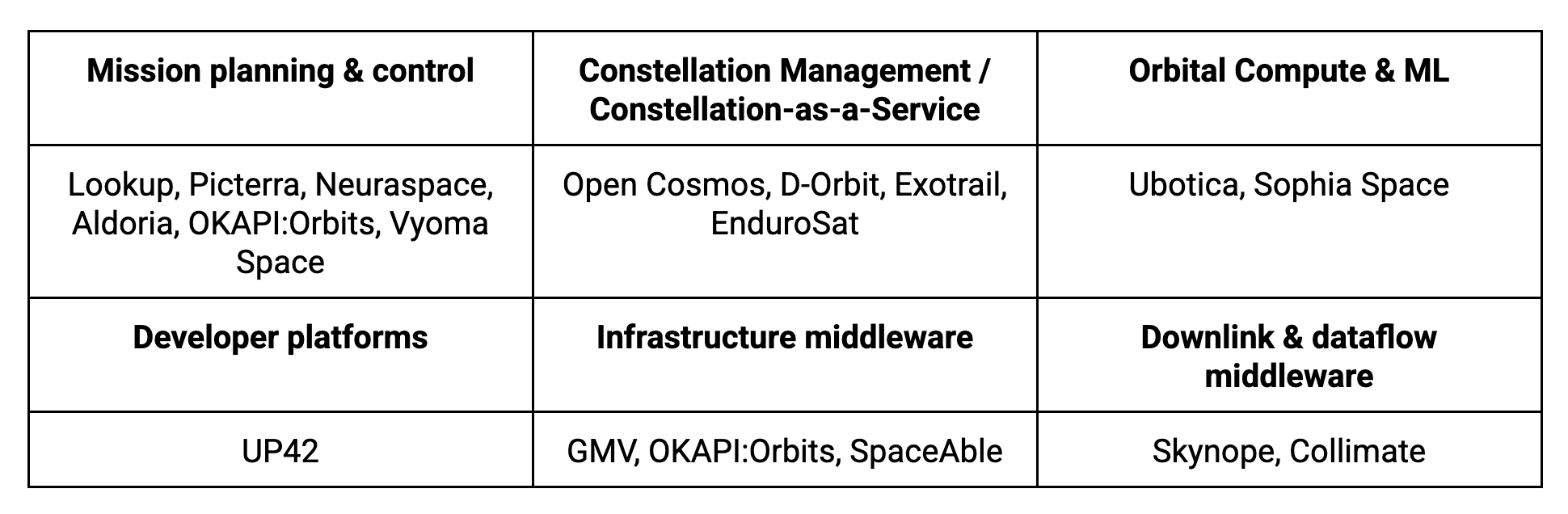

The real value of Earth Observation (EO) data has long been debated. For years, the promise of “insight from above” outpaced compelling commercial applications, with most demand anchored in defense and scientific research. However, today, that is beginning to shift. As revisit rates accelerate, data becomes richer and cheaper, and machine learning improves interpretation, new markets are emerging. The question is no longer whether EO data has value, but whether the ecosystem has matured enough to convert that into scalable businesses. Early signs, from climate risk analytics to commodity intelligence, suggest that the long-promise potential of EO may finally be entering its time.

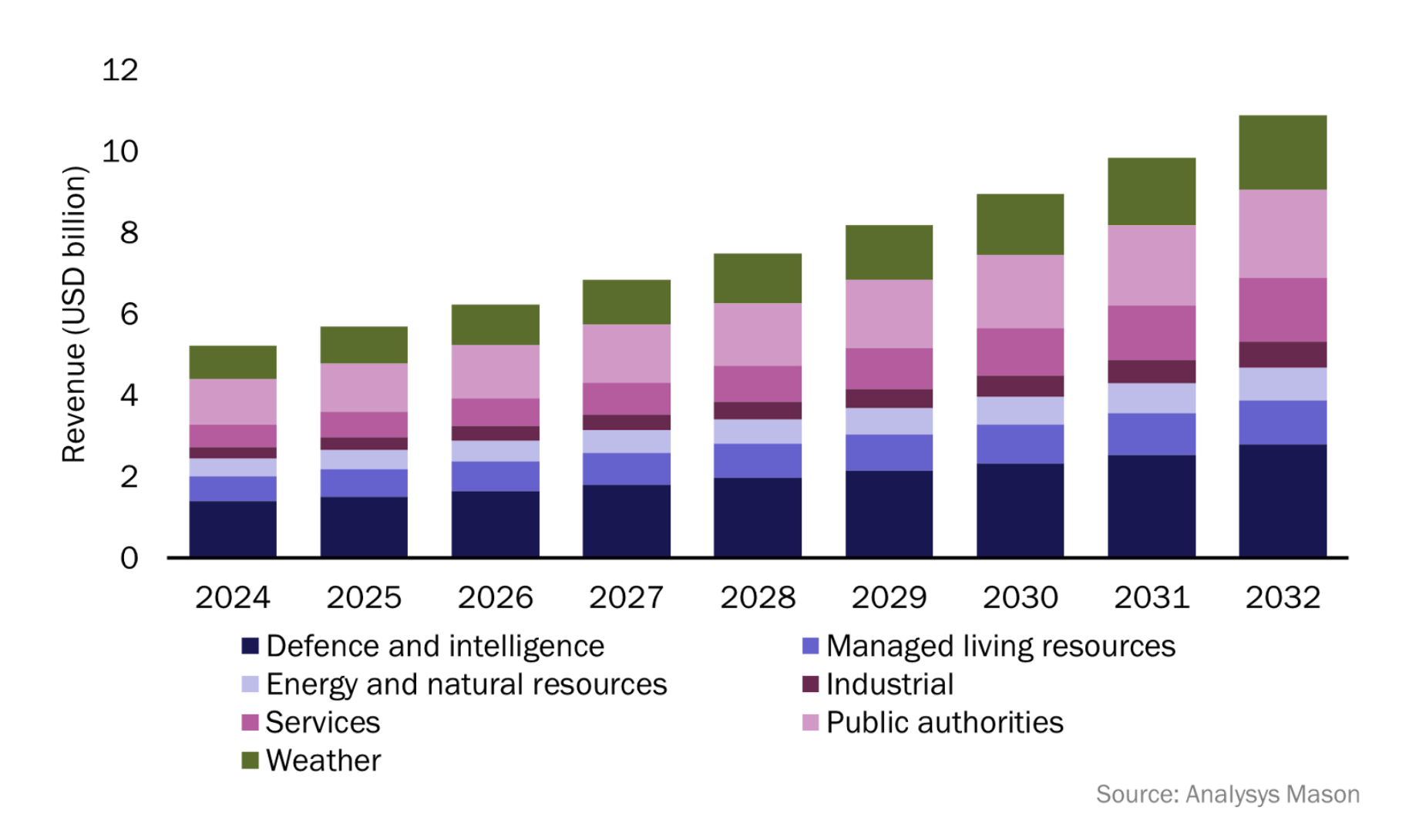

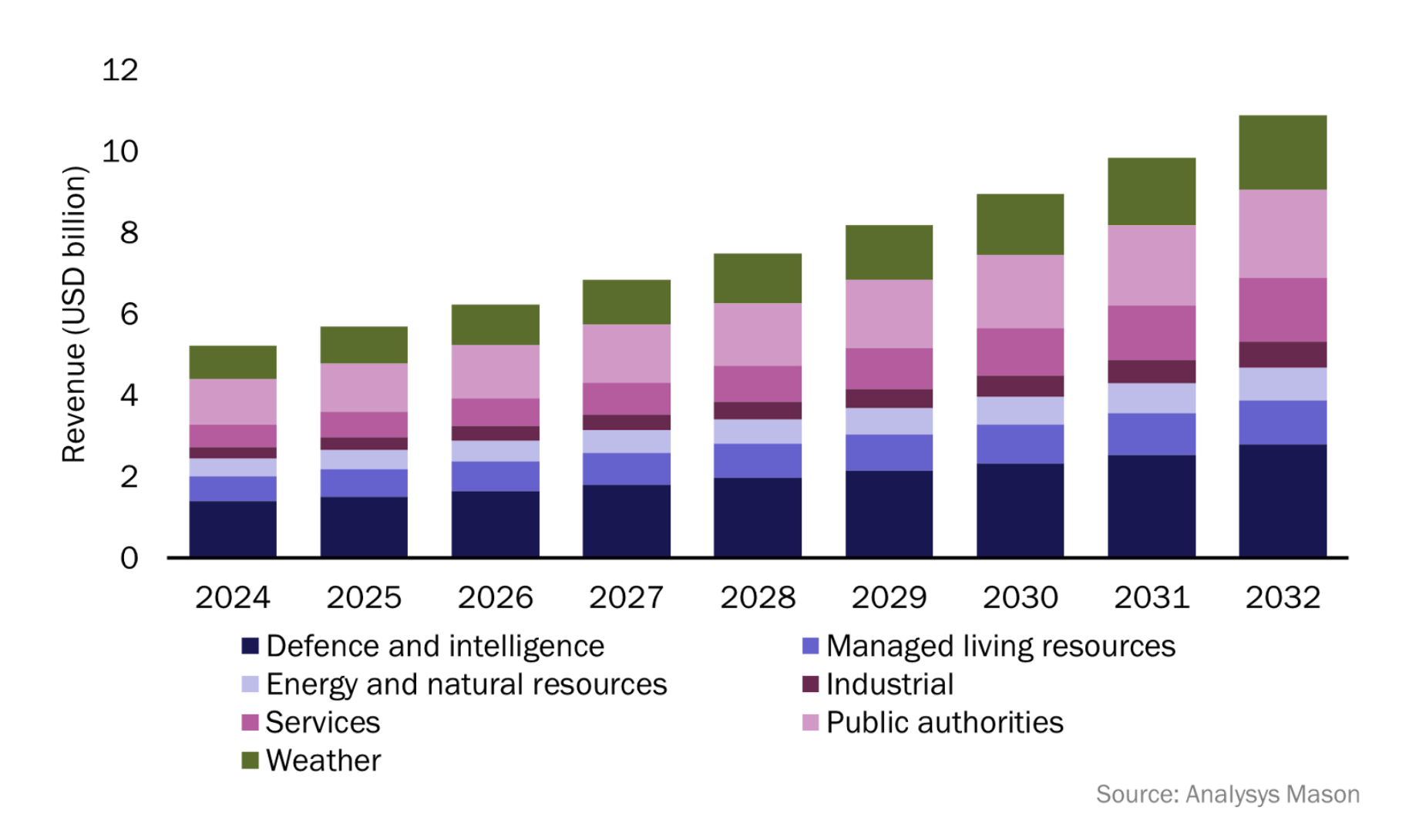

The U.S. still leads in many areas of space innovation, particularly when it comes to deep capital markets and commercial scale. But Europe is starting to play a stronger hand, especially in infrastructure and dual-use technologies. Several factors are driving this shift:

Europe has captured roughly 20% of global upstream space VC funding since 2020, ranking second behind the US, which still attracts around 3x more capital. There’s still a gap in capital depth compared to the U.S., and Europe’s challenge will be scaling startups to global markets without losing strategic alignment. As our portfolio company Lookup quoted:

“Space technology is shifting from a niche for pioneers to a backbone for global security and industry. Europe has the talent and the ambition, but must build solutions that are fast, sovereign, and trusted. At Look Up, we see our role as making space data not just available, but operational.

But the direction is clear: Europe’s edge won’t come from mimicking NASA or SpaceX. It will come from building globally competitive companies rooted in autonomy, interoperability, and real-world utility.

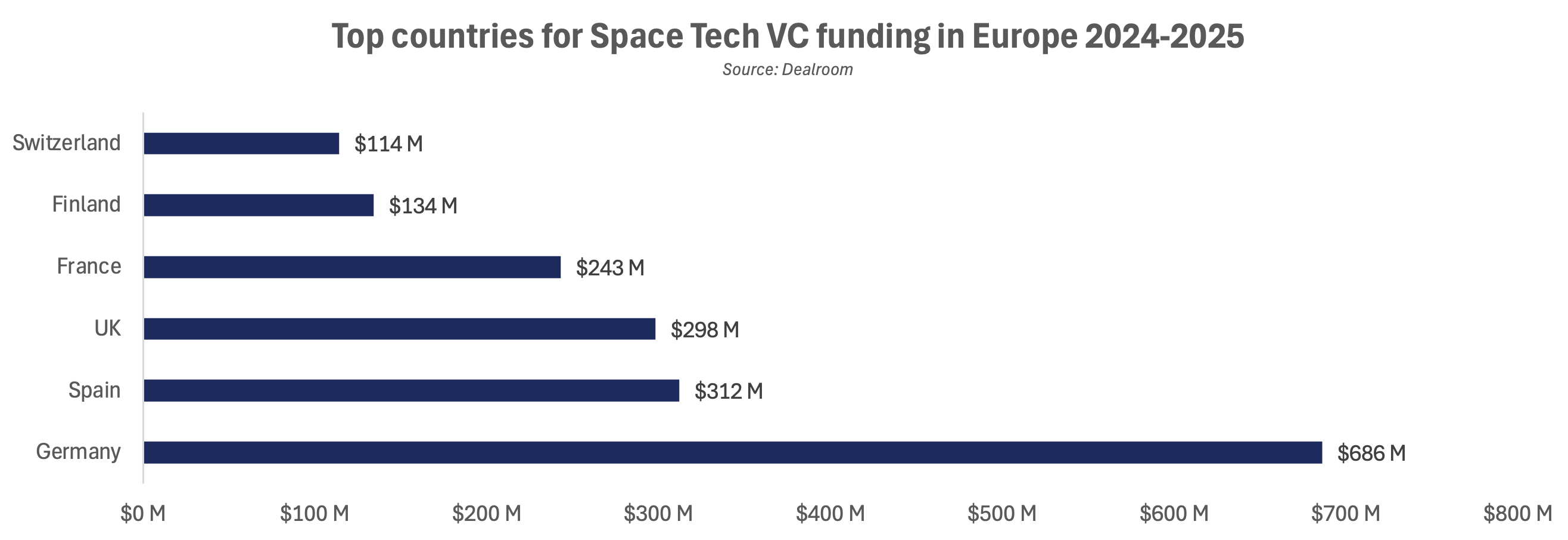

Spain’s SpaceTech industry has matured rapidly in the past decade, now ranking among Europe’s top SpaceTech ecosystems by VC funding and transforming into a credible ecosystem spanning launch, satellite manufacturing, propulsion, and downstream services.

Compared to European leaders like France, Germany, and the UK, where government budgets, industrial heritage, and large primes dominate; Spain’s advantage lies in its nimble, commercially oriented startups such as PLD Space, Sateliot, and Pangea Propulsion. The country benefits from targeted public co-funding and EU programs, but total domestic space budgets remain smaller, making venture capital and strategic partnerships critical for growth.

Spain’s space activity has accelerated markedly in recent years. Since 2021, the number of Spanish objects launched into orbit has more than doubled, rising from 21 payloads to 69 in 2024, reflecting the momentum of a new generation of space startups alongside established players. In some cases, this growth has been achieved with remarkably limited capital; for example, FOSSA Systems has already deployed more than 20 satellites with less than €10M in total funding. This progress has been accompanied by key institutional developments, including the creation of the national space agency (Agencia Espacial Española, AEE) and the launch of targeted public funding programs. As part of these efforts, more than €30M in contractual funding has already been awarded to startups such as Open Cosmos under the “Atlantic Constellation” initiative, with a further €300M announced for “Atlantic Constellation Plus.”

We’ve mapped the Spanish SpaceTech startup ecosystem in a live Airtable (link here), which we’ll continue updating as the ecosystem evolves, please feel free to reach out if we’re missing any companies! Finally, some of the most notable SpaceTech funding rounds in Spain over the past year include Aistech Space’s €8.5M raise, Kreios Space’s €8M seed round, and Pangea Propulsion €23M Series A.

Even as we warm up to space infra as a category, we’re trying to keep our enthusiasm in check. There are still reasons this hasn’t been a go-to area for generalist funds and some of those reasons still hold.

Without clear moats, we think it’s tough to underwrite breakout outcomes.

In short: We’re believers in the potential of this vertical but space is a hard business. It’s slower, messier, and more entangled with regulation than most of the markets we play in. That doesn’t make it unattractive. It just means it demands a different kind of conviction and likely a longer holding period.

With all that in mind, here’s where we’re starting to look more actively:

We’re not trying to predict who builds the next SpaceX. That’s not our lane. But we’re increasingly interested in the companies that make space useful for teams that don’t think of themselves as space companies at all.

That’s where we think the real opportunity might lie: in turning what was once a specialized, distant vertical into something that quietly becomes infrastructure.

---

This space is also rather new in our scope and we’d love to hear your thoughts and learn more about the trends that you are seeing. Do contact us at pablo@kfund.vc or paula@kfund.vc as we’d love to have an exchange with you.

Following our first investment in space and satellite tech, Lookup, we’ve been taking the time to dig deeper into the category and its evolving dynamics. We’re still early in our journey; learning, asking questions and updating our mental models as we go, but we wanted to share a first sketch of what’s capturing our attention. We’ve learned a lot from our extensive conversations with Silviu Pirvu FRSA and our friends at Arkadia Space and FOSSA Systems, but please reach out to pablo@kfund.vc or paula@kfund.vc to share your thoughts, feedback and perspectives as we keep exploring.

For some time, “SpaceTech” was often shorthand for “not our mandate.” Not because the ideas lacked merit, but because the risks seemed outsized, the timelines too long, exit pathways unclear, and the capital requirements over time exceeded the scale of our funds. When we heard “space,” we thought of enormous upfront costs, long R&D cycles, regulatory red tape, and decades of government-driven procurement. Even for funds with an appetite for frontier tech, space often sat just beyond the edge of what felt feasible.

But that framing is starting to shift, and not just for us. As our portfolio company Lookup puts it, the industry is evolving from an era of expensive launch and manufacturing into a more service-oriented, infrastructure-like model. Hardware remains critical, and there is significant innovation in areas like solar arrays, propulsion, and power management systems. At the same time, we see a major unlock at the data, integration, and workflow layers, where space becomes an enabler for adjacent sectors such as defense, insurance, energy, logistics, and mobility.

What used to feel like a highly specialized, capital-intensive domain is slowly becoming more modular, more software-driven, and most importantly for us, more investable. This change is not happening overnight and not without caveats but the distance between what’s happening in space and the industries we know well is closing.

This post is a working view of what feels like a turning point, where technical abstraction, commercial demand, and a new generation of startups are coming together to redraw the landscape.

Until recently, tapping into space-based assets meant working through long procurement cycles, complex hardware, and massive budgets. Now, that’s changing. Just as cloud abstracted away server management, a new generation of companies is abstracting the complexity of space. You no longer need to build or operate a satellite to benefit from it. Increasingly, you can:

This shift, from raw hardware to usable platforms, is making space relevant to entirely new user groups.

Now, while this transformation is real, it’s worth recognizing that the fundamental structure of the space economy has remained over time: satellites collect data, space tech companies process and deliver that data, and downstream businesses across industries like agriculture, defense or logistics, use it to inform decisions and power services. That loop hasn’t changed. What’s changed is how efficiently, affordably, and flexibly each part of that loop can now operate.

Several enabling technologies and have accelerated this shift:

Launch and satellite building costs were long a bottleneck on satellite deployment, but over the past two decades the dynamic has shifted, with thousands now launched each year. We are entering an era of far more affordable space infrastructure. The result is a larger and more diverse orbital fleet, creating a broader and more accessible data ecosystem, and with it, business models that were never conceived before.

So while satellites and other physical infrastructure remain central, what’s changed is how much easier it’s become to access and work with that infrastructure. APIs, onboard compute, and integration tools have further removed layers of complexity. Space is no longer just for governments and deep-tech primes, and that shift is what’s opening the door to new commercial use cases and broader investor interest.

A few companies building the underlying tech driving this shift that stood out to us:

Collectively, these examples point to the same shift: value is increasingly captured not just in the hardware itself, but in the layers that make space infrastructure easier to deploy, integrate, and use across industries.

This is how we currently view the industry, with some illustrative examples from Spain and the rest of Europe. We’re still learning, and would love your thoughts on other ways of viewing the taxonomy of the landscape:

Core infrastructure providers

The upstream enablers positioned in service of end-user outcomes

Enabling platforms & middleware

Companies that abstract complexity and make space data useful across verticals

As space infrastructure becomes more abstracted and accessible, its value is increasingly defined by what it enables on the ground. This isn’t just about satellites in orbit, it’s about insight at street level. The most exciting momentum is happening in the tools, platforms and workflows that deliver space-derived intelligence to its real users: governments responding to crises, insurers pricing risk, farmers optimizing yield and logistics teams navigating port delays.

As Silviu Pirvu FRSA, Chairman & CTO Optimal Cities puts it: “The world is continuously changing, in some places faster than before. Shaping a healthy and thriving future needs reliable, actionable perspectives to ensure the resilience of people, assets, and environments. Delayed decisions lead to their obsolescence, with ripple effects in society, economy and environment. When combined with AI and user friendliness, SpaceTech can be a critical ally for authorities, decision-makers, professionals and emergency responders in enabling fast, decisive action - from Earth Observation to real-time communications, energy beaming and safe orbits.”

The real value of Earth Observation (EO) data has long been debated. For years, the promise of “insight from above” outpaced compelling commercial applications, with most demand anchored in defense and scientific research. However, today, that is beginning to shift. As revisit rates accelerate, data becomes richer and cheaper, and machine learning improves interpretation, new markets are emerging. The question is no longer whether EO data has value, but whether the ecosystem has matured enough to convert that into scalable businesses. Early signs, from climate risk analytics to commodity intelligence, suggest that the long-promise potential of EO may finally be entering its time.

The U.S. still leads in many areas of space innovation, particularly when it comes to deep capital markets and commercial scale. But Europe is starting to play a stronger hand, especially in infrastructure and dual-use technologies. Several factors are driving this shift:

Europe has captured roughly 20% of global upstream space VC funding since 2020, ranking second behind the US, which still attracts around 3x more capital. There’s still a gap in capital depth compared to the U.S., and Europe’s challenge will be scaling startups to global markets without losing strategic alignment. As our portfolio company Lookup quoted:

“Space technology is shifting from a niche for pioneers to a backbone for global security and industry. Europe has the talent and the ambition, but must build solutions that are fast, sovereign, and trusted. At Look Up, we see our role as making space data not just available, but operational.

But the direction is clear: Europe’s edge won’t come from mimicking NASA or SpaceX. It will come from building globally competitive companies rooted in autonomy, interoperability, and real-world utility.

Spain’s SpaceTech industry has matured rapidly in the past decade, now ranking among Europe’s top SpaceTech ecosystems by VC funding and transforming into a credible ecosystem spanning launch, satellite manufacturing, propulsion, and downstream services.

Compared to European leaders like France, Germany, and the UK, where government budgets, industrial heritage, and large primes dominate; Spain’s advantage lies in its nimble, commercially oriented startups such as PLD Space, Sateliot, and Pangea Propulsion. The country benefits from targeted public co-funding and EU programs, but total domestic space budgets remain smaller, making venture capital and strategic partnerships critical for growth.

Spain’s space activity has accelerated markedly in recent years. Since 2021, the number of Spanish objects launched into orbit has more than doubled, rising from 21 payloads to 69 in 2024, reflecting the momentum of a new generation of space startups alongside established players. In some cases, this growth has been achieved with remarkably limited capital; for example, FOSSA Systems has already deployed more than 20 satellites with less than €10M in total funding. This progress has been accompanied by key institutional developments, including the creation of the national space agency (Agencia Espacial Española, AEE) and the launch of targeted public funding programs. As part of these efforts, more than €30M in contractual funding has already been awarded to startups such as Open Cosmos under the “Atlantic Constellation” initiative, with a further €300M announced for “Atlantic Constellation Plus.”

We’ve mapped the Spanish SpaceTech startup ecosystem in a live Airtable (link here), which we’ll continue updating as the ecosystem evolves, please feel free to reach out if we’re missing any companies! Finally, some of the most notable SpaceTech funding rounds in Spain over the past year include Aistech Space’s €8.5M raise, Kreios Space’s €8M seed round, and Pangea Propulsion €23M Series A.

Even as we warm up to space infra as a category, we’re trying to keep our enthusiasm in check. There are still reasons this hasn’t been a go-to area for generalist funds and some of those reasons still hold.

Without clear moats, we think it’s tough to underwrite breakout outcomes.

In short: We’re believers in the potential of this vertical but space is a hard business. It’s slower, messier, and more entangled with regulation than most of the markets we play in. That doesn’t make it unattractive. It just means it demands a different kind of conviction and likely a longer holding period.

With all that in mind, here’s where we’re starting to look more actively:

We’re not trying to predict who builds the next SpaceX. That’s not our lane. But we’re increasingly interested in the companies that make space useful for teams that don’t think of themselves as space companies at all.

That’s where we think the real opportunity might lie: in turning what was once a specialized, distant vertical into something that quietly becomes infrastructure.

---

This space is also rather new in our scope and we’d love to hear your thoughts and learn more about the trends that you are seeing. Do contact us at pablo@kfund.vc or paula@kfund.vc as we’d love to have an exchange with you.